“The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.” ~Milan Kundera

On April 1st the Idaho Falls Post Register included a piece by Jakob Thorington. The article celebrates sixteen years of successful clean-up work at the Idaho National Laboratory (INL), but it fails to mention key information, leaving the reader with an incomplete view of this historic moment.

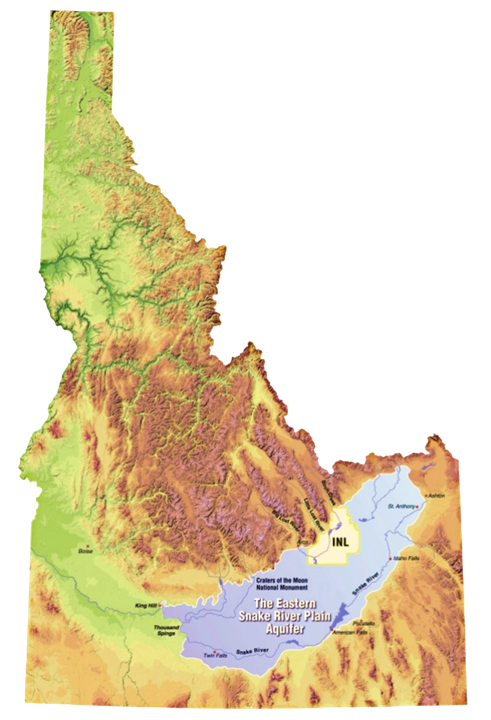

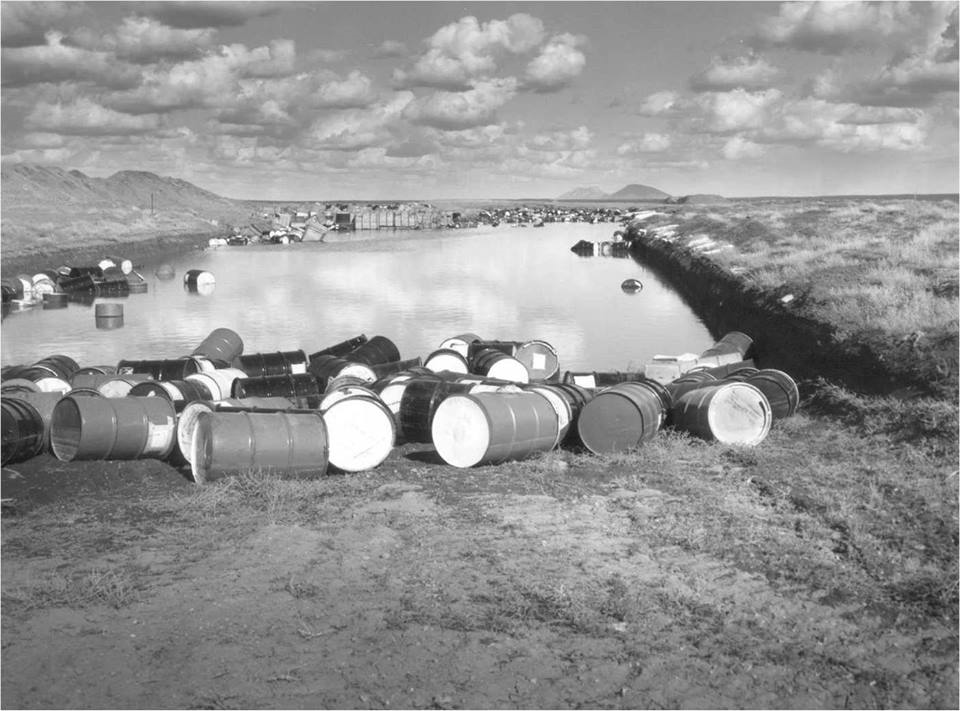

Thorington reports that 10,000 cubic meters of targeted waste were exhumed and repackaged for shipment to a salt cavern in New Mexico but makes no mention of the far larger quantities of radioactive waste that were left in the ground above our aquifer. The excavators that did the digging along with the massive tents (all now contaminated) will be buried beneath the man-made cap that will cover the entire 97 acres.

The article’s celebratory tone runs along, seemingly oblivious to the fact that the ground above the Snake River Aquifer remains deeply toxic and will have to be monitored for countless generations. Now that the clean-up efforts – at least the more active work of digging and repackaging have been completed, there’s a finality to the mistakes of the past that could and should ring through this moment, that is, if the lessons of the past are to be absorbed and if the wheels of progress could pause long enough to listen.

Thorington’s curated look at reality suggests that when it comes to nuclear waste, there never was a real problem – at least not one that we couldn’t fix with dedication, courage and ingenuity. Surely these qualities were present throughout the clean-up program. But the article would have us believe that once the area is capped the problem disappears. This idea of “bury it and it will disappear” is an old one and in this case, it plays into the hands of the nuclear industry, but it’s also human nature.

Confronted with our own helplessness in regard to nuclear waste, who wouldn’t want to sidestep the whole affair? No one knows what to do with the stuff so we look the other way while continuing to create more of it in a seemingly endless cycle of repetition and avoidance. As a professional mental health counselor, I can’t help but think that at the core of every stuck, toxic cycle is a place no one wants to see, let alone go there. But bearing witness to the painful reality is the first step towards healing. As we breathe and live into those once closed-off spaces, new possibilities emerge. We become more human and more related to each other and to the systems that sustain us.

When I first came to this issue, I wasn’t thinking about it in terms of our collective humanity, but as an activist. I was deeply concerned by what I’d heard about the past handling of radioactive waste: the injection wells that until the 1980’s sent low-level waste directly into the Snake River Aquifer, and the burying of waste in unlined pits overtop of the aquifer. And so, in 2012 as a board member of the local environmental activist group, the Snake River Alliance, I went on my first tour of the INL’s radioactive clean-up sites.

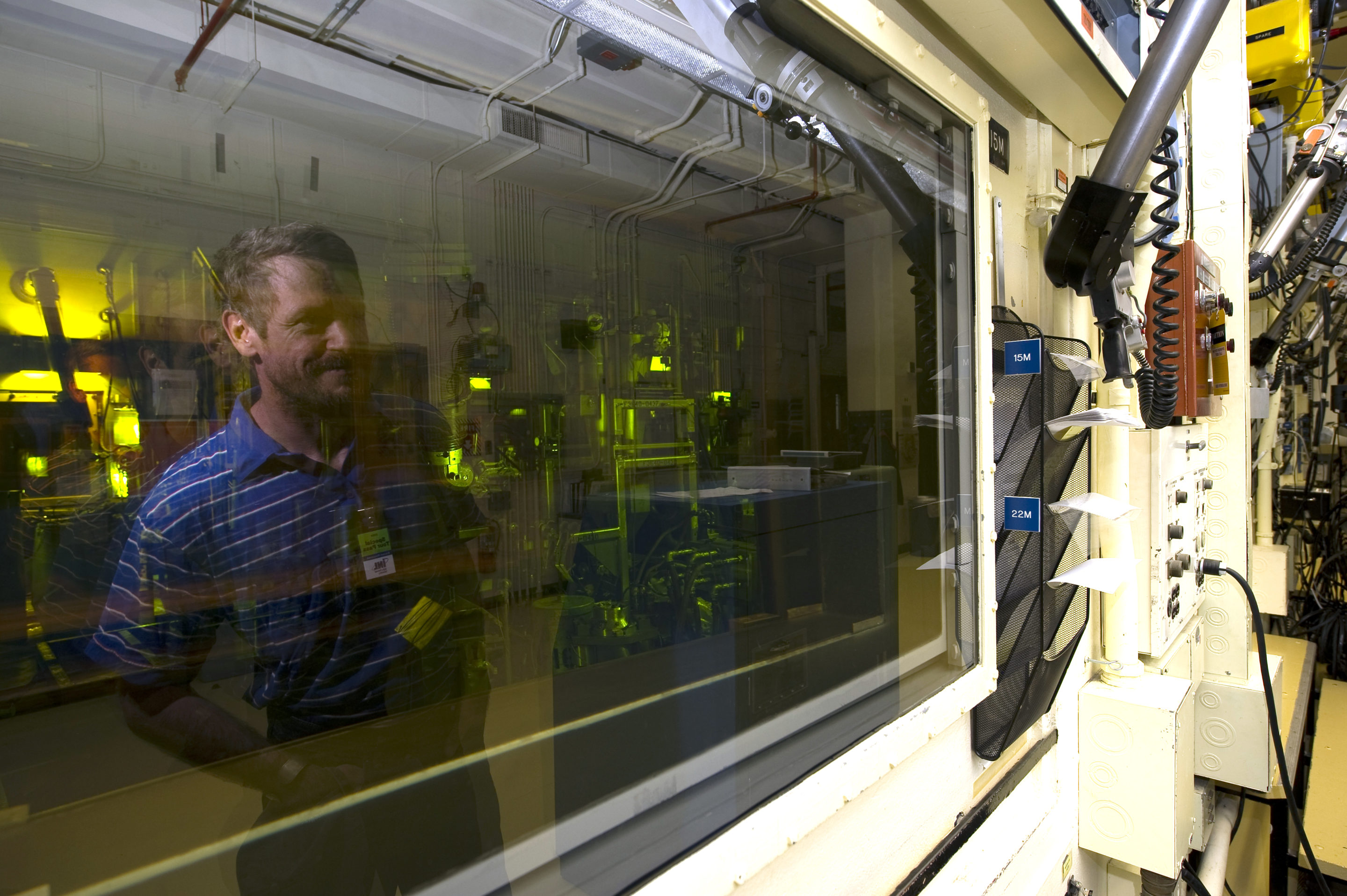

I saw men and women with their hands in glove boxes sorting the unearthed waste that had originally come from Rocky Flats Colorado where for 40 years they milled plutonium triggers for nuclear bombs. A friend of mine on the tour was remembering stories of her mom who had died from cancer after working at Rocky Flats. Her mom had worked as a secretary, but told of daily scans with Geiger counters, which more often than one would hope, ended up with everyone immediately relocating to a new office (of course taking their coffee along with them). That was the 1960’s and a bit of stray radiation apparently wasn’t perceived as such a big deal. The fantasy of technological progress as our saving grace had a new poster child. Nuclear power was the silver bullet poised to fix any problem a person could think of, from wart removal to aircrafts that could stay aloft for weeks at a time, to energy too cheap to meter. Menus with desserts that included date pudding were developed for the nuclear airplanes that never made it off the ground.

In a 2020 LINE commission (Leaders In Nuclear Energy) meeting, Kristine Svinicki, the former chairwoman of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission made an impassioned pro-nuclear plea, telling INL engineers, nuclear contractors and pro-nuclear bureaucrats that with just one football field of radioactive waste, girls around the world could be educated instead of being stuck at home doing menial labor. The dream of nuclear salvation lives on. My friend on the tour told me that her mom remained a firm believer in nuclear power until she got sick and then she was confused and dismayed.

In the 1960’s, in the throes of the Cold War, the waste was barely an afterthought. Today, after billions of tax dollars spent in clean-up (and still counting), the waste remains an afterthought. At least the industry would have it that way. Flohr, the main contractor of the clean-up work at the INL, referring to the burial grounds commented: “Hopefully when you drive down the highway, you won’t even know about the things we did here.” The crossroads before us is not about waste management. Those decisions have all been made. Instead, it’s about the story we tell (or don’t tell) concerning what went on in that place. The implications are profound because it’s the story we tell that determines how we move forward from here.

In one of my visits to the sites I got to see the workers getting suited up in multiple layers of suits, preparing to step into the oxygen-supplied cabs of the excavators. I stood in the ante-chamber to those vast tented spaces, designed so that the air always blows inward to where the waste was being exhumed and I imagined I felt the nerves of those waiting to begin their shift. I felt deeply grateful for them and the work they were doing for all of us.

When we try to wipe our hands of the past aren’t we also forgetting the men and women who day in and day out put their health on the line to diminish the threat of toxicity for future generations? The crossroads is before us. To move forward as if nothing happened leaves part of ourselves behind, and our forgetfulness becomes a recipe for repeating the mistakes of the past. The alternative is less comfortable at first, but when we live with what we can’t make right, it becomes a profound teacher. It points us in the direction of our humanity as well as our humility. This ship we’re on is bigger than we are and nuclear waste in its unmanageability and its dissonance is a constant reminder of where we’ve stepped out of line, and it will continue to teach its lessons for a long, long time.

Tim Andreae, LCPC serves on the Snake River Alliance board of directors. For more information about our board click here.